Inside the Universe Machine: The Webb Space Telescope’s Trailblazing Optics

[ad_1]

“Build something that will absolutely, positively work.” This was the mandate from NASA for designing and building the James Webb Space Telescope—at 6.5 meters wide the largest space telescope in history. Last December, JWST launched famously and successfully to its observing station out beyond the moon. And now according to NASA, as soon as next week, the JWST will at long last begin releasing scientific images and data.

Mark Kahan, on JWST’s product integrity team, recalls NASA’s engineering challenge as a call to arms for a worldwide team of thousands that set out to create one of the most ambitious scientific instruments in human history. Kahan—chief electro-optical systems engineer at Mountain View, Calif.–based Synopsys—and many others in JWST’s “pit crew” (as he calls the team) drew hard lessons from three decades ago, having helped repair another world-class space telescope with a debilitating case of flawed optics. Of course the Hubble Space Telescope is in low Earth orbit, and so a special space-shuttle mission to install corrective optics (

as happened in 1993) was entirely possible.

Not so with the JWST.

The meticulous care NASA demanded of JWST’s designers is all the more a necessity because Webb is well out of reach of repair crews. Its mission is to study the infrared universe, and that requires shielding the telescope and its sensors from both the heat of sunlight and the infrared glow of Earth. The best place to do that is while parked in one of the few reliably stable orbits in the Earth–moon system—a mostly empty patch of interplanetary space 1.5 million kilometers away (well beyond the moon’s orbit) at a spot physicists call the

second Lagrange point, or L2.

The pit crew’s job was “down at the detail level, error checking every critical aspect of the optical design,” says Kahan. Having learned the hard way from Hubble, the crew insisted that every measurement on Webb’s optics be made in at least two different ways that could be checked and cross-checked. Diagnostics were built into the process, Kahan says, so that “you could look at them to see what to kick” to resolve any discrepancies. Their work had to be done on the ground, but their tests had to assess how the telescope would work in deep space at cryogenic temperatures.

Three New Technologies for the Main Mirror

Superficially, Webb follows the design of all large reflecting telescopes. A big mirror collects light from stars, galaxies, nebulae, planets, comets, and other astronomical objects—and then focuses those photons onto a smaller secondary mirror that then ultimately directs the light to instruments that record images and spectra.

Webb’s

6.5-meter primary mirror is the first segmented mirror to be launched into space. All the optics had to be made on the ground at room temperature but were deployed in space and operated at 30 to 55 degrees above absolute zero— also known as 0 Kelvin. “We had to develop three new technologies” to make it work, says Lee D. Feinberg of the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, the optical telescope element manager for Webb for the past 20 years.

The longest wavelengths that Hubble has to contend with were 2.5 micrometers, whereas

Webb is built to observe infrared light that stretches to 28 μm in wavelength. Compared to Hubble, whose primary mirror is a circle of an area 4.5 square meters, “[Webb’s primary mirror] had to be 25 square meters,” says Feinberg. Webb also “needed segmented mirrors that were lightweight, and its mass was a huge consideration,” he adds. No single-component mirror that could provide the required resolution would have fit on the Ariane 5 rocket that launched JWST. That meant the mirror would have to be made in pieces, assembled, folded, secured to withstand the stress of launch, then unfolded and deployed in space to create a surface that was within tens of nanometers of the shape specified by the designers.

The James Webb Space Telescope [left] and the Hubble Space Telescope side by side—with Hubble’s 2.4-meter-diameter mirror versus Webb’s array of hexagonal mirrors making a 6.5-meter-diameter light-collecting area. NASA Goddard Space Flight Center

The James Webb Space Telescope [left] and the Hubble Space Telescope side by side—with Hubble’s 2.4-meter-diameter mirror versus Webb’s array of hexagonal mirrors making a 6.5-meter-diameter light-collecting area. NASA Goddard Space Flight Center

NASA and the

U.S. Air Force, which has its own interests in large lightweight space mirrors for surveillance and focusing laser energy, teamed up to develop the technology. The two agencies narrowed eight submitted proposals down to two approaches for building JWST’s mirrors: one based on low-expansion glass made of a mixture of silicon and titanium dioxides similar to that used in Hubble and the other the light but highly toxic metal beryllium. The most crucial issue came down to how well the materials could withstand temperature changes from room temperature on the ground to around 50 K in space. Beryllium won because it could fully release stress after cooling without changing its shape, and it’s not vulnerable to the cracking that can occur in glass. The final beryllium mirror was a 6.5-meter array of 18 hexagonal beryllium mirrors, each weighing about 20 kilograms. The weight per unit area of JWST’s mirror was only 10 percent of that in Hubble. A 100-nanometer layer of pure gold makes the surface reflect 98 percent of incident light from JWST’s main observing band of 0.6 to 28.5 μm. “Pure silver has slightly higher reflectivity than pure gold, but gold is more robust,” says Feinberg. A thin layer of amorphous silica protects the metal film from surface damage.

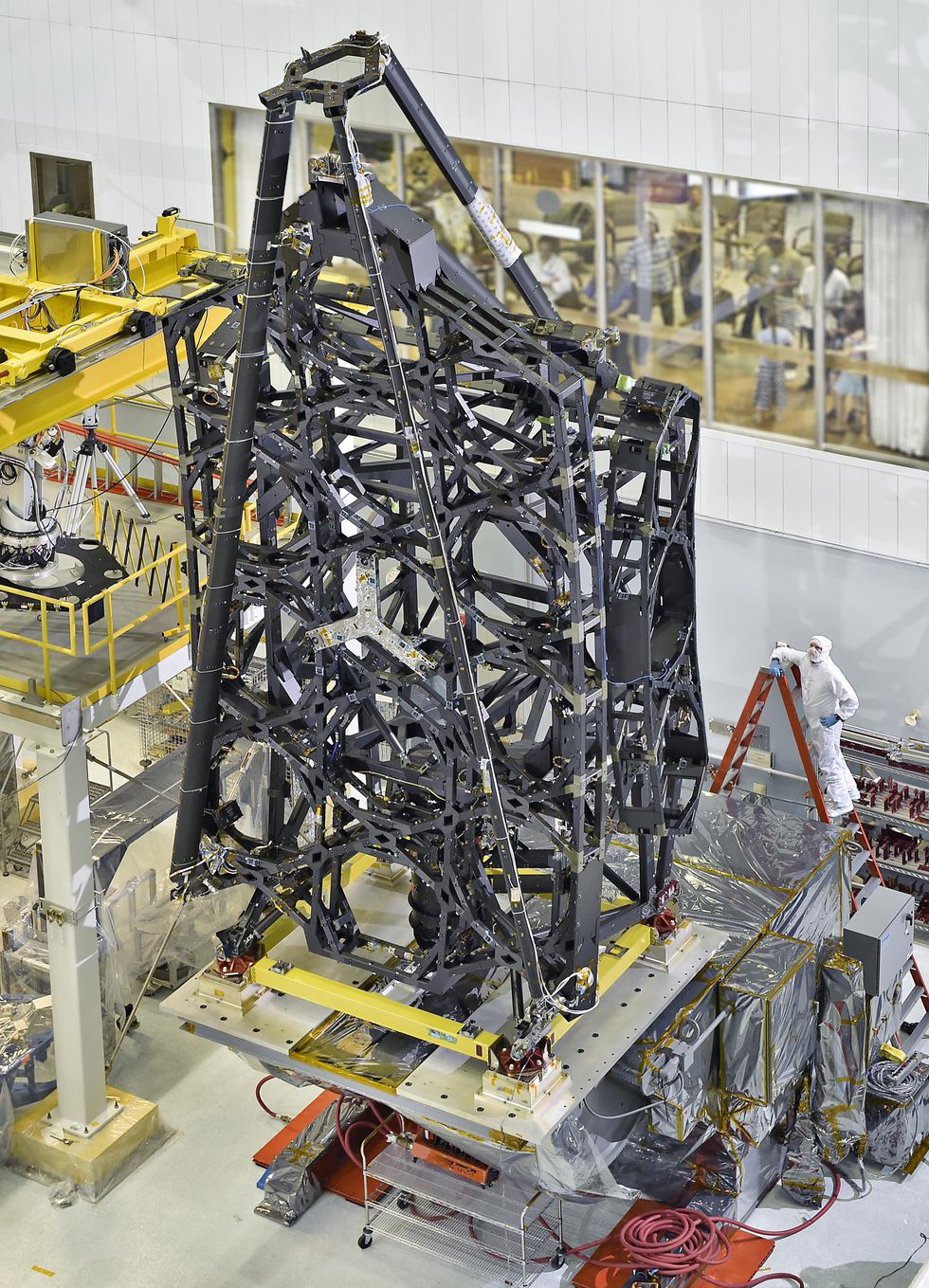

In addition, a wavefront-sensing control system keeps mirror segment surfaces

aligned to within tens of nanometers. Built on the ground, the system is expected to keep mirror alignment stabilized throughout the telescope’s operational life. A backplane kept at a temperature of 35 K holds all 2.4 tonnes of the telescope and instruments rock-steady to within 32 nm while maintaining them at cryogenic temperatures during observations.

The JWST backplane, the “spine” that supports the entire hexagonal mirror structure and carries more than 2,400 kg of hardware, is readied for assembly to the rest of the telescope. NASA/Chris Gunn

The JWST backplane, the “spine” that supports the entire hexagonal mirror structure and carries more than 2,400 kg of hardware, is readied for assembly to the rest of the telescope. NASA/Chris Gunn

Hubble’s amazing, long-exposure images of distant galaxies are made possible by

gyroscope wheels spinning at 320 revolutions per second; the wheels are part of the gimbals that aim and stabilize the telescope as it stares at its targets in the sky. However, those gimbals have to move the whole space observatory, and that wears out the gyroscopes, which have been replaced repeatedly. Only three of the Hubble’s six gyros remain operational today, and NASA has devised plans for operating with one or two gyros at reduced capability. Hubble uses reaction wheels when it needs to move the telescope to look at different parts of the sky.

Webb also uses

reaction wheels to turn across the sky, but instead of using mechanical gyros to sense direction, it uses optical gyroscopes with no moving parts. Rather than have gimbals move the whole telescope for fine tracking to keep stars steady, Webb tilts a small fine-steering mirror in the optical path over an angle of just 5 arc seconds. Those very fine adjustments of the light path into the instruments keep the telescope on target. “It’s a really wonderful way to go,” says Feinberg, adding that it compensates for small amounts of jitter without having to move the whole 6-tonne observatory.

Instruments

Other optics distribute light from the fine-steering mirror among four instruments, two of which can observe simultaneously. Three instruments have sensors that observe wavelengths of 0.6 to 5 μm, which astronomers call the near-infrared. The fourth, called the Mid-InfraRed Instrument (MIRI), observes what astronomers call the mid-infrared spectrum, from 5 to 28.5 μm. Different instruments are needed because sensors and optics have limited wavelength ranges. (Optical engineers may blanch slightly at astronomers’ definitions of what constitutes the near- and mid-infrared wavelength ranges. These two groups simply have differing conventions for labeling the various regimes of the infrared spectrum.)

Mid-infrared wavelengths are crucial for observing

young stars and planetary systems and the earliest galaxies, but they also pose some of the biggest engineering challenges. Namely, everything on Earth and planets out to Jupiter glow in the mid-infrared. So for JWST to observe distant astronomical objects, it must avoid recording extraneous mid-infrared noise from all the various sources inside the solar system. “I have spent my whole career building instruments for wavelengths of 5 μm and longer,” says MIRI instrument scientist Alastair Glasse of the Royal Observatory, in Edinburgh. “We’re always struggling against thermal background.”

Mountaintop telescopes can see the near-infrared, but observing the mid-infrared sky requires telescopes in space. However, the thermal radiation from Earth and its atmosphere can cloud their view, and so can the telescopes themselves unless they are cooled far below room temperature. An ample supply of liquid helium and an orbit far from Earth allowed the

Spitzer Space Telescope’s primary observing mission to last for five years, but once the last of the cryogenic fluid evaporated in 2009, its observations were limited to wavelengths shorter than 5 μm.

Webb has an elaborate solar shield to block sunlight, and an orbit 1.5 million km from Earth that can keep the telescope to below 55 K, but that’s not good enough for low-noise observations at wavelengths longer than 5 μm. The near-infrared instruments operate at 40 K to minimize thermal noise.

But for observations out to 28.5 μm, MIRI uses a specially developed closed-cycle, helium cryocooler to keep MIRI cooled below 7 K. “We want to have sensitivity limited by the shot noise of astronomical sources,” says Glasse. (Shot noise occurs when optical or electrical signals are so feeble that each photon or electron constitutes a detectable peak.) That will make MIRI 1,000 times as sensitive in the mid-infrared as Spitzer.

Another challenge is the limited transparency of optical materials in the mid-infrared. “We use reflective optics wherever possible,” says Glasse, but they also pose problems, he adds. “Thermal contraction is a big deal,” he says, because the instrument was made at room temperature but is used at 7 K. To keep thermal changes uniform throughout MIRI, they made the whole structure of gold-coated aluminum lest other metals cause warping.

Detectors are another problem. Webb’s near-infrared sensors use mercury cadmium telluride photodetectors with a resolution of 2,048 x 2,048 pixels. This resolution is widely used at wavelengths below 5 μm, but sensing at

MIRI’s longer wavelengths required exotic detectors that are limited to offering only 1,024 x 1,024 pixels.

Glasse says commissioning “has gone incredibly well.” Although some stray light has been detected, he says, “we are fully expecting to meet all our science goals.”

NIRcam Aligns the Whole Telescope

The near-infrared detectors and optical materials used for observing at wavelengths shorter than 5 μm are much more mature than those for the mid-infrared, so the Near-Infrared Camera (NIRcam) does double duty by both recording images and aligning all the optics in the whole telescope. That alignment was the trickiest part of building the instrument, says NIRcam principal investigator

Marcia Rieke of the University of Arizona.

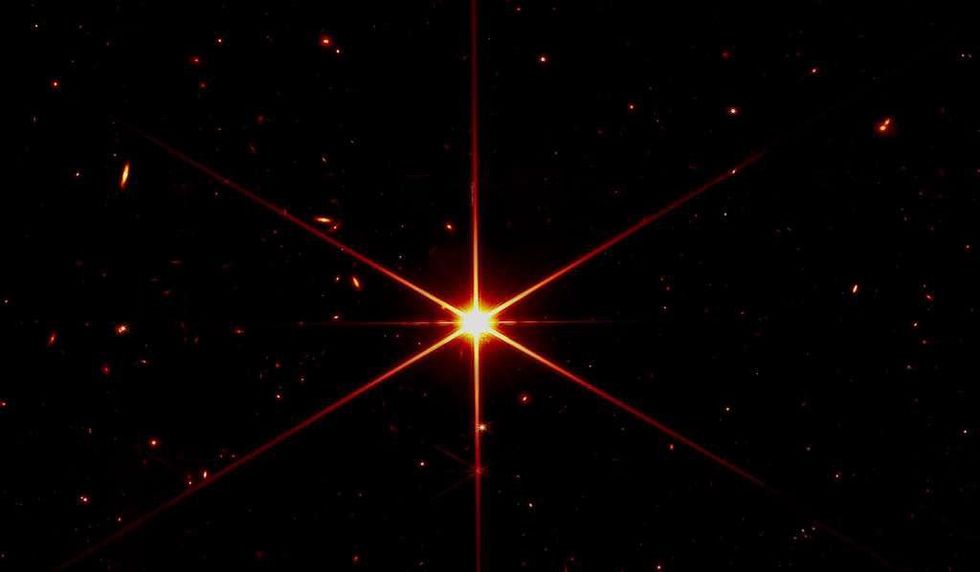

Alignment means getting all the light collected by the primary mirror to get to the right place in the final image. That’s crucial for Webb, because it has 18 separate segments that have to overlay their images perfectly in the final image, and because all those segments were built on the ground at room temperature but operate at cryogenic temperatures in space at zero gravity. When NASA recorded a test image of a single star after Webb first opened its primary mirror, it showed 18 separate bright spots, one from each segment.

When alignment was completed on 11 March, the image from NIRcam showed a single star with six spikes caused by diffraction.

Even when performing instrumental calibration tasks, JWST couldn’t help but showcase its stunning sensitivity to the infrared sky. The central star is what telescope technicians used to align JWST’s mirrors. But notice the distant galaxies and stars that photobombed the image too!NASA/STScI

Even when performing instrumental calibration tasks, JWST couldn’t help but showcase its stunning sensitivity to the infrared sky. The central star is what telescope technicians used to align JWST’s mirrors. But notice the distant galaxies and stars that photobombed the image too!NASA/STScI

Building a separate alignment system would have added to both the weight and cost of Webb, Rieke realized, and in the original 1995 plan for the telescope she proposed designing NIRcam so it could align the telescope optics once it was up in space as well as record images. “The only real compromise was that it required NIRcam to have exquisite image quality,” says Rieke, wryly. From a scientific point, she adds, using the instrument to align the telescope optics “is great because you know you’re going to have good image quality and it’s going to be aligned with you.” Alignment might be just a tiny bit off for other instruments. In the end, it took a team at Lockheed Martin to develop the computational tools to account for all the elements of thermal expansion.

Escalating costs and delays had troubled Webb for years. But for Feinberg, “commissioning has been a magical five months.” It began with the sight of sunlight hitting the mirrors. The segmented mirror deployed smoothly, and after the near-infrared cameras cooled, the mirrors focused one star into 18 spots, then aligned them to put the spots on top of each other. “Everything had to work to get it to [focus] that well,” he says. It’s been an intense time, but for Feinberg, a veteran of the Hubble repair mission, commissioning Webb was “a piece of cake.”

NASA announced that between May 23rd and 25th, one segment of the primary mirror had been dinged by a micrometeorite bigger than the agency had expected when it analyzed the potential results of such impacts. “Things do degrade over time,” Feinberg said. But he added that Webb had been engineered to minimize damage, and NASA said the event had not affected Webb’s operation schedule.

From Your Site Articles

Related Articles Around the Web

Source link